The Bible has a number of structural and formatting features. Some of these features are known to most readers of the Bible. However, there are some formatting features which are less known but quite significant for interpretation.

The Bible has two major structural and formatting features. First, the Bible is divided into Testaments, books, chapters, and verses, which aid memory. Second, the biblical text is formatted to indicate whether the text is prose or poetry, alerting the reader to poetic features that aid interpretation.

Let’s look at each structural and formatting feature in turn.

Divisions of the Bible

The Bible is a large book. Thankfully, those dedicated to its preservation, reading, and studying have helpfully divided the Bible to aid the reader. From biggest divisions to smallest divisions, the Bible is formatted as follows: Testaments –> Books –> Chapters –> Verses. The word order has not been changed. For those who find the chapter and verse divisions annoying or unhelpful, there are Bibles published without them. Let’s take a brief look at each division.

The Bible is Divided into Two Testaments

The Bible is divided into two testaments: the Old Testament and the New Testament. Simply put, the Old Testament covers God’s salvation work before Jesus’ incarnation, while the New Testament covers God’s salvation work after Jesus’ incarnation. For more information as to why there are two testaments and why one is called “Old” and the other “New,” see my article here.

Dividing the Bible into two testaments allows the reader to clearly see the major turning point in salvation history. The promised messiah – Jesus – has come to forgive sins, right all the wrongs in the world, and set up his eternal kingdom. The two testaments also help the reader identify the part of the Bible that aligns closest to his place in salvation history. We live in the era after Jesus’ ascension and before Jesus’ second coming. Much of the New Testament treats that unique place in salvation history.

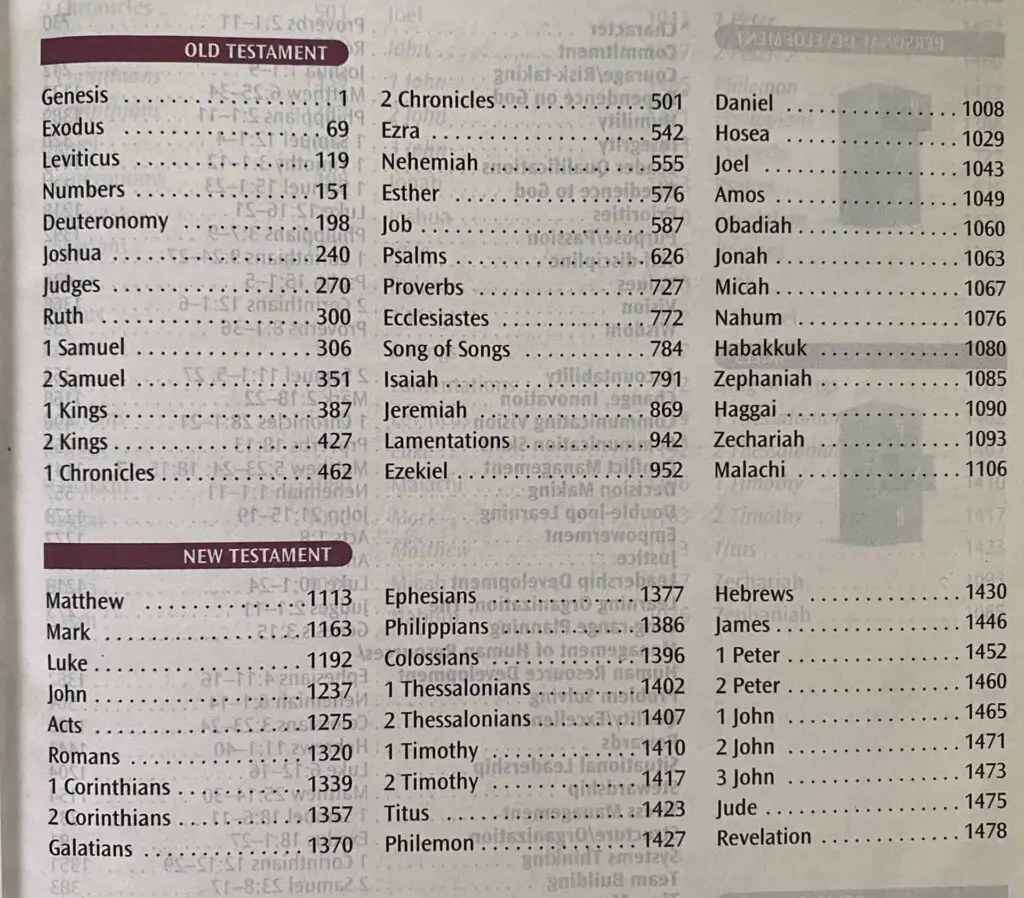

The Bible is Divided into Books

The Bible is divided into 66 ‘books.’ Of course, not every ‘book’ is a book; some are letters (such as Philippians and 2 John), some are collections of poems and songs (such as the Book of Psalms, also called the Psalter), and so forth. The division of the Bible into books acknowledges that the Bible was written by multiple human authors and that the Bible is a collection of different written works over a lengthy period of time (see my article here on the authorship of the Bible).

Understanding that the Bible is a collection of different written works can aid interpretation. For example, if Paul (a biblical author) uses a word that can mean a couple different things, we can search all the letters of Paul to see how he used that particular word elsewhere. This is what I did when assessing what Paul says about obeying governments (click here to see that article).

Dividing the Bible into books also aids memorization of content. It is much easier to remember where something is located in the Bible if you can remember in what book it is found. Further, conversing with others about the Bible becomes easier when we can point to a certain book of the Bible.

The Bible is Divided into Chapters

Each book of the Bible (with the exception of the shortest books: Obadiah, 2 John, 3 John, and Jude) has been divided into chapters. The chapter numbers begin anew in each book of the Bible. For the most part, these chapters divide the book into logical sections based on the content of the book. For example, Genesis 22 recounts the story of when God asked Abraham to sacrifice Isaac and Genesis 38 recounts the story of how Judah’s line was preserved when it was in danger of dying out (Judah is important because Jesus comes from his line). The New Testament chapters are also logical sections in their books. For example, 1 Corinthians 13 is about the topic of love, while 1 Corinthians 15 is about the topic of the resurrection.

So, the chapter divisions help the reader understand the content of the book by dividing the text into logical sections based on topic or argument (for the most part). Chapter divisions also aid our memory so that we can more easily and accurately recall where a particular text is located in the Bible.

For how the chapters and chapter divisions came about, see my article here.

The Bible is Divided into Verses

Each book of the Bible has been further divided into verses. The verse divisions begin anew with each chapter. The only oddity to this is the books with no chapters: Obadiah, 2 John, 3 John, and Jude. These books only have verses with verse 1 starting at the beginning of the book. For the most part, the verses divide the chapters into smaller logical sections. Verses are most commonly found between sentences or clauses. 1 Corinthians 12:1–3 is a good example:

“1) Now concerning spiritual gifts, brothers, I do not want you to be uninformed. 2) You know that when you were pagans you were led astray to mute idols, however you were led. 3) Therefore I want you to understand that no one speaking in the Spirit of God ever says “Jesus is accursed!” and no one can say “Jesus is Lord” except in the Holy Spirit.”

1 CORINTHIANS 12:1–3

As you can tell, the verse numbers come at the end of each sentence.

Like chapter divisions, verse divisions help the reader understand the content of the book by dividing the text into logical smaller sections based on grammar (for the most part). Verse divisions also aid our memory so that we can more easily and accurately recall where a particular text is located in the Bible.

For how the verses and verse divisions came about, see my article here.

Prose and Poetic Formatting

A key feature in most English Bibles about which many Christians are unaware is the formatting for prose and poetry. The editors and translators have determined which parts of the biblical text are prose and which parts are poetry and have formatted the text accordingly so that the reader can easily see the difference. Let’s look at each in turn.

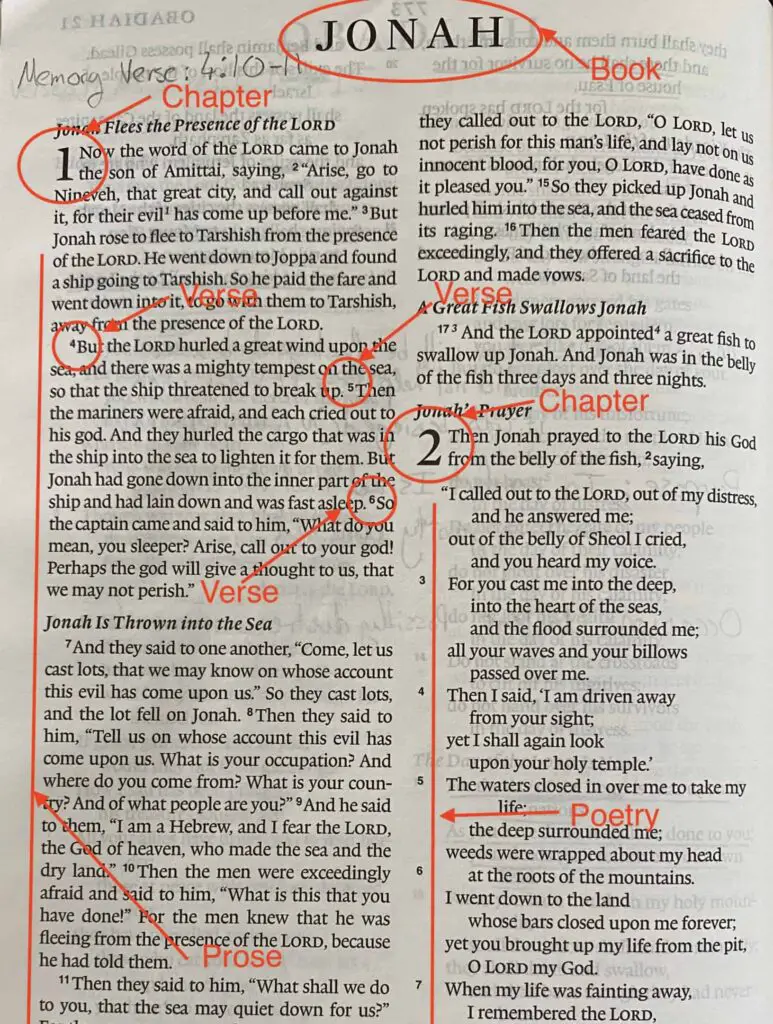

Prose Formatting

The historical books in the Old Testament, the Gospels, and the New Testament letters are for the most part written in prose, with elements of poetry scattered throughout.

To indicate which sections are prose, most English Bibles format the text in blocks with the left and right side of each column flush.

The only time the text is not flush is when a new paragraph begins. To indicate a new paragraph, most Bibles will indent the first line.

When a text is prose, there will be fewer poetic features, meaning the text can usually be read plainly (i.e., what is said is what is meant). This becomes important in some key doctrinal texts. For example, Genesis 1 is formatted as prose, which lends strength to the claim that each day is a literal 24-hour day (see my article on that topic here). The crossing of the Red Sea in Exodus 14 is formatted as prose, which lends strength to the claim that God parted the Sea, the Israelites walked across on dry ground, and the Egyptians who followed drowned when God put the waters back in their place. Finally, the Resurrection of Jesus from the dead in Matthew 28, Luke 24, and John 20 are formatted as prose, suggesting that the resurrection actually happened.

Poetic Formatting

Probably of more significance is the poetic formatting of modern English Bibles. If you look at the formatting of Genesis and then look through the formatting of the Psalms or most of the prophetic books, you should notice that there is a significant difference. The Book of Psalms, most of the wisdom literature, and most of the prophetic literature in the Bible are poetry. The editors of our Bibles have intentionally formatted these works to reflect this poetic nature. Not only is the formatting intentional, but it usually follows the formatting of the Hebrew in the BHS (Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia) and the Greek in the UBS (United Bible Societies) and NA (Nestle-Aland) editions.

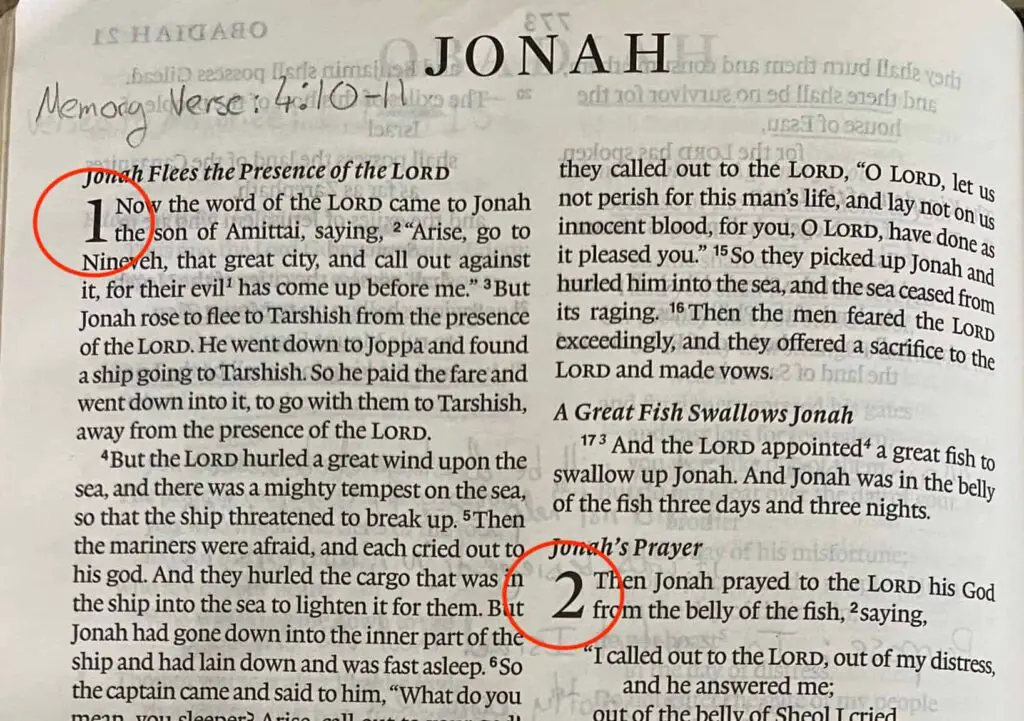

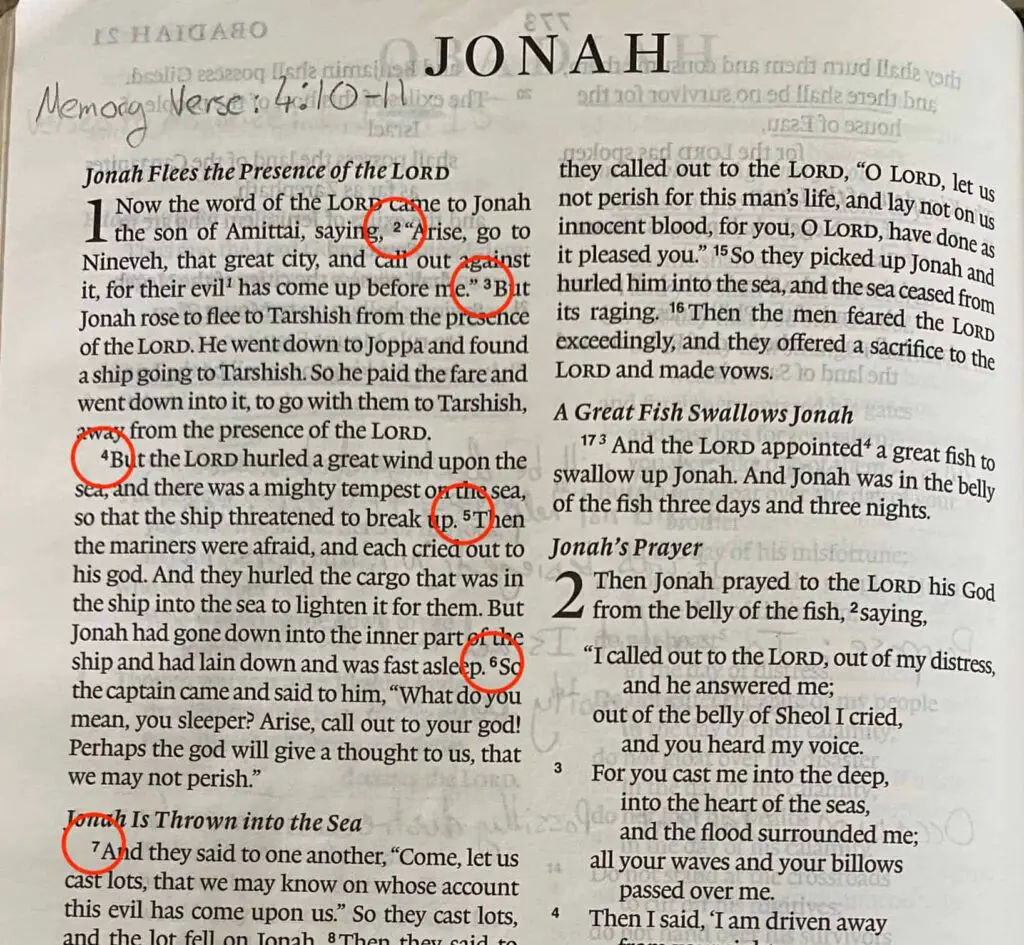

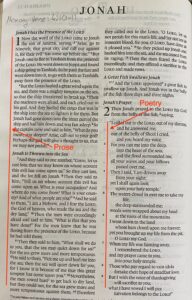

The key difference between prose formatting and poetry formatting is that prose is in block form, whereas poetry has a lot of indentations on the right and left hand sides. The prose and poetic formatting is seen easily in the book of Jonah. Chapter 1 is prose and chapter 2 is poetry.

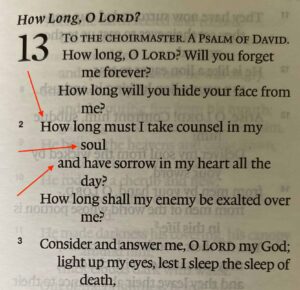

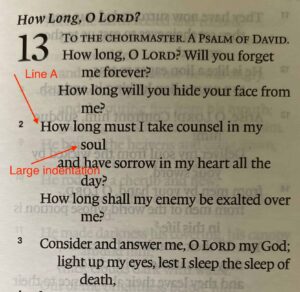

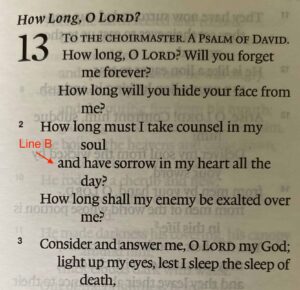

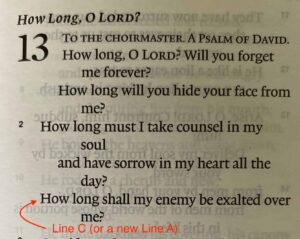

What do the indentations mean in the poetic formatting? Let’s take a look at Psalm 13:2 as our example.

First, you should notice that Psalm 13:2 has three different indentations. Each indentation is telling us something about this verse and the relationship between the words.

Second, Psalm 13:2 has three ‘Lines’ (‘Lines’ is a technical term here, which is why I am capitalizing it). Line A is “How long must I take counsel in my soul.” Notice that “soul” is indented further than the following word “and.” That furthest indentation indicates that there is not a new line, but that there was not enough room to include “soul” with Line A.

Third, Line B (“and have sorrow in my heart all the day?” ) is indented further than Line A (“How long . . .”) because there is a parallelism (relationship) between Lines A and B. The two lines share the verb “How long must I” and so are closely related. It is up to you to discern the relationship between the two lines.

Fourth, “How long shall my enemy be exalted over me?” is not indented at all. You could label this either a new Line A or Line C. Thus, you could say Psalm 13:2 contains a couplet (Lines A and B) and a single Line (a new Line A). Or you could say Psalm 13:3 contains a triplet (Lines A, B, and C) and that all three lines are related. Again, it is up to you to discern the relationship between the lines. Personally, I think it is a Line C and we have a triplet.

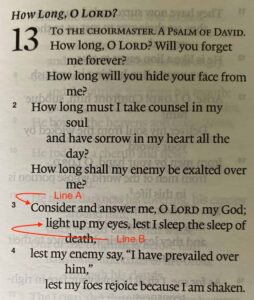

If we move onto Psalm 13:3, we see that there is a couplet. The editor believes both Lines are related to each other because the editor slightly indented Line B.

- Line A: “Consider and answer me, O LORD my God”

- Line B: “light up my eyes, lest I sleep the sleep of death”

What you as the reader need to answer is, “what is the relationship between Lines A and B?” It is also important to note that new Lines in a new verse may be related to the Lines in a previous verse.

The poetic formatting is important for a number of reasons. First, it indicates relationships between lines that may otherwise not be apparent. Thus, you the reader need to take greater care and time while reading poetry to ensure you are understanding the message of the author. Second, upon realizing you are reading poetry, you need to be aware of poetic features, such as figures of speech. For example, Psalm 40:2 says the following:

“He drew me up from the pit of destruction, out of the miry bog, and set my feet upon a rock, making my steps secure.”

PSALM 40:2, emphasis added

In Psalm 40:2, we need to ask ourselves whether or not David was literally in a destroying pit and/or a miry bog. Also, did Yahweh literally take David out of a miry bog and set him upon a literal rock? Or, is David using figures of speech to colourfully and accurately recount his troubles and how God helped him? Because the formatting of Psalm 40 tells us it is poetry, we the readers need to be open to poetic features. For the record, David is most likely saying that he was in dire trouble and would soon die if the Lord did not come and help him; but the Lord did come and help. As such, Psalm 40:2 employs figurative language that still accurately describes David’s situation and God’s help.

Summary and Concluding Thoughts

The Bible’s format is produced by modern editors. The original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek manuscripts did not have formatting such as we have in our Bibles. In fact, they didn’t even have punctuation! Because the Bible’s formatting is a product of modern editors, it should be used with caution and not understood as divinely inspired. With that being said, I think the testament–verse formatting is extremely helpful in aiding memory and the prose/poetry formatting is extremely helpful in accurately interpreting the text.