Have you ever wondered where the chapter and verse numbers in your Bible came from? Who put them there? If you have studied Greek and Hebrew at all, you may also be wondering, why are there slight differences between the versification of the English Bibles and those of the original languages (Hebrew and Greek)? This is the topic I will address in this article.

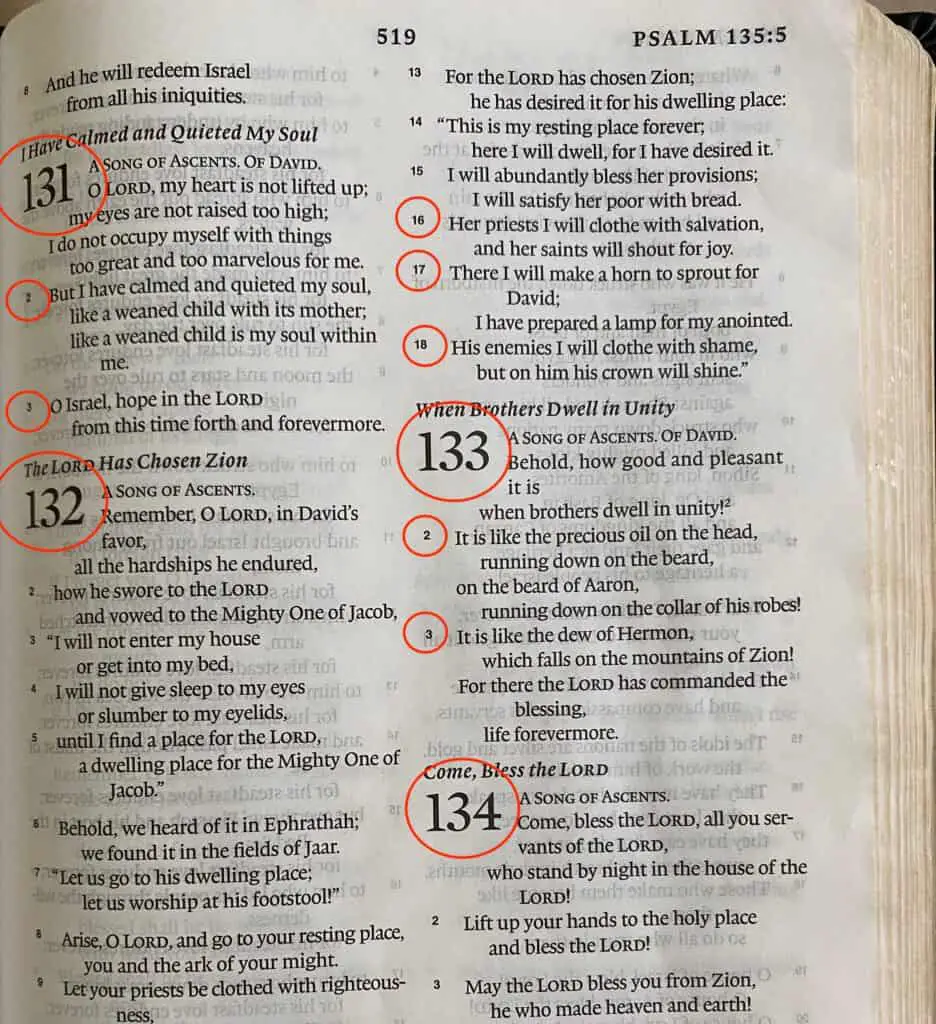

The first English Bible to have chapter and verse divisions was the Geneva Bible of 1560, which employed Stephen Langton’s chapter divisions, the Ben Asher family’s Old Testament verse divisions, and Robert ‘Stephanus’ Estienne’s New Testament verse divisions.

Believe it or not, yes, there was a time that the bible had no chapters or verses. Early Christians and Jews cited Scripture by referencing the biblical author, the book, or a notable/recognizable event in the biblical text. For example, when Jesus is debating the Sadducees about the resurrection, he cites Exodus 3:6 in the following manner:

“And as for the dead being raised, have you not read in the book of Moses, in the passage about the bush, how God spoke to him, saying, ‘I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob’?”

MARK 12:26, emphasis added

I will take a developmental approach to the topic of versification in this article, beginning with the Hebrew Old Testament, then moving to the Greek New Testament, and concluding with the English Bible. For those only interested in the English Bible versification, click HERE to jump to that section.

Dividing the Hebrew Old Testament

The oldest complete copy of the Hebrew Bible (also called the Hebrew Old Testament) dates back to the early 11th-century AD. This is commonly called the Masoretic text (MT). The Masoretic text divides the text three different ways, whereas modern English Bibles divide it two ways (chapters and verses).

First, the Masoretic text began a new topic (a main subdivision) on a new line, while leaving the last line of the previous unit blank. The Masoretes called this an פרשה פתוחה (“open section” or “open paragraph”) to refer to a main subdivision.

In late-medieval manuscripts, main subdivisions were marked with the letter פ because that is the letter that begins פתוחה (“open”).

Second, the Masoretic text began a unit smaller than a main subdivision by inserting a space nine letters long on the line between the two units. The Masoretes called this a פרשה סתומה (“closed section” or “closed paragraph”).

In late-medieval manuscripts, smaller units were marked with the letter ס because that is the letter that begins סתומה (“closed”).

Both the “open section” and “closed section” division system and the exegetical decisions for dividing the text is quite ancient (see Emanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, 3rd edition revised and expanded, 2012: 48–49, 198–201).

Third, the Masoretes divided the text into verses with a silluq (׃) at the end of each verse. The verse divisions were transmitted orally, so are not found in the Qumran scrolls (see Tov, 198–99). However, the concept of a verse, or a pasuq, is known from the Talmud. Further, the rabbis were accustomed to a fixed division of the biblical text into verses (see L. Blau, “Massoretic Studies, III.-IV.: The Division into Verses,” JQR 9 (1897): 122–44, 471–90; and Tov, 49).

As can be seen, the Hebrew Bible has a long history of being divided into sections. This will affect the versification of the Hebrew Bible as printed in the modern BHS (Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia), which is a printed copy of the 11th-century Leningrad Codex (B19a).

Dividing the Greek New Testament

Chapter divisions in the Greek New Testament date as far back as the 4th-century AD, evidenced in the 4th-century Codex Vaticanus. Codex Vaticanus divided the text where there were breaks in sense. For example, there are 170 divisions in Matthew, 62 in Mark, 152 in Luke, and 80 in John. Chapters in the Pauline letters are numbered continuously as if Paul’s letters were one book.

There were other systems for dividing the Greek text into chapters that came later than Codex Vaticanus. Unfortunately, none of these systems were used in the versification of the Greek New Testament of the Nestle-Aland (NA) or United Bible Society (UBS) versions of the Greek New Testament. This is in part because there was no universal standard and in part because the Greek New Testament is an eclectic text not based on any particular manuscript.

Further, the Greek New Testament was not divided into anything smaller than chapters before Robert “Stephanus” Estienne divided the text (see below).

Modern Chapter and Verse Divisions

Chapter Divisions

The chapter divisions in all current English Bibles (OT & NT) were added to the Bible by Stephen Langton (AD 1150–1228). He was a lecturer at the University of Paris and became the Archbishop of Canterbury in the early 13th century AD. Langton added the chapter divisions to the Latin text. These divisions were almost universally accepted and were applied to all English Bibles down to the present day.

The earliest manuscript containing Langton’s divisions is the 13th century Paris manuscript 𝔇.

Langton’s chapter divisions frequently break the text at unnatural points, such as chapter 5 of Deuteronomy, which should have begun at 4:44, the start of Moses second discourse and chapter 11 of 1 Corinthians, which should have begun at 11:2. It has been argued that Langton attempted to create chapters of approximate equal length, which accounts for it breaking the text at unnatural points. This is something I have personally noticed.

Verse Divisions

The verse divisions in all current English New Testaments were added Robert “Stephanus” Estienne, printer from Paris. Estienne added the verses to a Latin/Greek diglot of the New Testament while travelling from Paris to Lyons. Estienne’s son commented that Estienne divided the New Testament into verses while travelling inter equitandum. Some have understood the Latin inter equitandum to mean “on horseback” and suggest that Estienne divided the text while actually on horseback, which accounts for some of the unnatural breaks in the text (see Hebrews 3:10 in the Greek NT). However, it is more likely that Estienne’s son meant his father divided the text while resting at various inns along the way/during the trip.

Estienne’s versification of the Greek and Latin New Testament made its way into all English Bibles to the current day with some slight modifications where warranted. For example, Hebrews 3:10 in the Greek begins with the phrase “for forty years,” which was made part of 3:9 in all English Bibles.

Prior to Estienne’s versification, biblical scholars had to reference texts with phrases such as “halfway through Ephesians chapter 5.” For all its faults, Estienne provided a major advancement in the specificity of biblical citation.

The verse divisions in all current English Old Testaments are based on the Masoretes divisions of the Hebrew text with the silluq (׃), which was standardized by the Ben Asher family around 900AD. When Langton’s chapter divisions were added to the Old Testament at a later date to the non-Hebrew Old Testaments, the verses divisions were conformed to fit into Langton’s scheme. However, this is not the case with the Hebrew Old Testament (see below). It should be noted that biblical scholars reference the Hebrew chapter and verse numbers, not the English, which may cause some confusion if you read academic commentaries, monographs, and articles.

The First English Bible with Chapters and Verses

The first English Bible to have chapter and verse divisions was the Geneva Bible of 1560, which employed Langton’s chapter divisions, the Ben Asher family’s OT verse divisions, and Estienne’s NT verse divisions.

Influence of Langton and Estienne on the Hebrew and Greek Bibles

The Hebrew Bible (Old Testament)

Langton’s chapter divisions were added to the Hebrew Old Testament by Salomon ben Ishmael around AD 1330. When Langton’s chapter divisions were added to the Hebrew Bible, the chapter divisions were at times adjusted to fit the Ben Asher scheme (see the differences between the English and Hebrew books of Joel and Malachi). The Masoretes’ versification was preferred in the Hebrew Bible because they do a better job at keeping the thought units together. Thus, there are some differences between the chapter and verse numbers of the Hebrew Old Testament and the English Old Testament.

The Greek New Testament

Langton’s chapter divisions and Estienne’s verse divisions were both adopted for the Greek New Testament, represented most widely in the Nestle-Aland (NA) and United Bible Society (UBS) versions. As noted above, there are some minor adjustments that the editors of these Bible’s make to the verses, but nothing as major as what the Hebrew Bible has.

Summary and Concluding Thoughts

The original autographs of the Bible, which is what was inspired, did not have any divisions. Divisions of whatever kind, including the modern chapter and verse divisions, came well after the initial writing of the biblical text. Thus, the chapter and verse divisions are not part of Scripture and are not inspired by God. Rather, they are helpful additions (like headings, see my article here) to the biblical text.

The chapter and verse divisions of the biblical text help us memorize and identify passages of Scripture with specificity. We no longer need to employ the “somewhere” phrase that is used in the book of Hebrews:

“It has been testified somewhere . . . .”

“For he has somewhere spoken of the seventh day in this way . . . .”

HEBREWS 2:6; 4:4

Understanding the history of chapter and verse divisions in the Bible and coming to the realization that the Hebrew OT, Greek NT, and English Bibles all have different versification should caution all Christians from playing ‘biblical mathematics’ by using the chapter and verse numbers to predict certain events, such as the return of Jesus.

So, let us praise God for the faithful men who took pains to divide the biblical text into (mostly) coherent sections for our benefit, but let us not put their work on the level of the biblical authors who were inspired by the Holy Spirit.

If you are interested in the development of the biblical text, I encourage you to check out these two books:

- Emanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, 3rd edition revised and expanded. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012.

- Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 4thedition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.